The logic of the syllogism and of Bayes’ theorem can be seen in light of a house and a condo, respectively.

The Logic of the Syllogism and a House for Sale

A house for sale would include the kitchen, while the kitchen would include each of its permanent elements, such as the cabinets, the flooring, and the sink. This is analogous to the syllogism in which an element (the sink), as part of the content of a subset (the kitchen) is thereby an element of the set (the house).

The Logic of Bayes’ Theorem and a Condo Unit for Sale

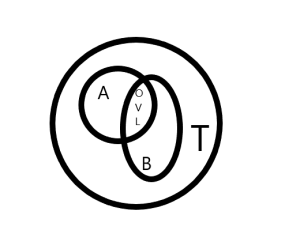

To effect an analogy between Bayes’ theorem and a condo unit for sale, let us identify the condo unit for sale as one of two condo units comprising area 3 of a condominium building, where the two units are defined each as including a utility room of area 3, common to both units.

The real estate agent, a devotee of Bayes’ theorem, tells a prospective customer:

- The condo unit for sale, 3A, is 15% of the entire condominium building’s floor space.

- The other unit of area 3, 3B, is 20% of the entire condominium building’s floor space.

- The common utility room of area 3 is 25% of unit 3B.

- By Bayes’ theorem, the common utility room is 1/3 of unit 3A, which is for sale.

The customer says, “That’s fine, but what is the square footage of the private rooms of unit 3A?” The agent replies, “It’s twice the square footage of the common utility room.” The customer notes, “That’s no help. If you don’t know the square footage of area 3, do you know the entire square footage of the building?” The agent gives up on this customer, saying, “Picky, picky, picky. You’re one of those who think that truth is absolute, when in fact human knowledge is relative. You probably think of logic as embodied in the syllogism, when the fullness of logic is relative and is truly expressed by Bayes’ theorem. Logic consists in weighing probabilities, the ratios of subsets to sets”

The agent then adopts a more conciliatory attitude, “You see much of human knowledge is that which we use for decision making, which is often the weighing of probabilities afforded us by Bayes’ theorem. I know that for a person in the condo building, the likelihood that the person is in the private quarters of unit 3A is a probability of 1/10. This knowledge is implied by Bayes’ theorem. I also know that a person, in condo unit 3A is likely to be in the private quarters thereof at a probability of 2/3. I could then weigh these probabilities in deciding whether unit 3A would suit my needs, if I bought it.” The prospective customer replies, “ I understand, but such relative knowledge is insufficient for me. I would not know the size of the private area of 3A, e.g. it could be 200 sq. ft. or 2000 sq. ft. The relative knowledge that the private quarters is 2/3 of its whole is insufficient for me.”